For Pioneer Valley residents, Carter’s term overshadowed by life of global human service

|

Published: 12-30-2024 4:30 PM

Modified: 12-30-2024 5:59 PM |

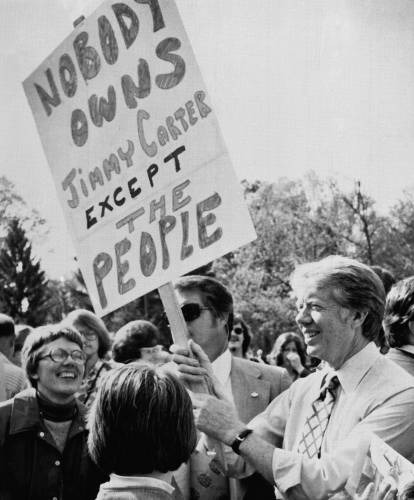

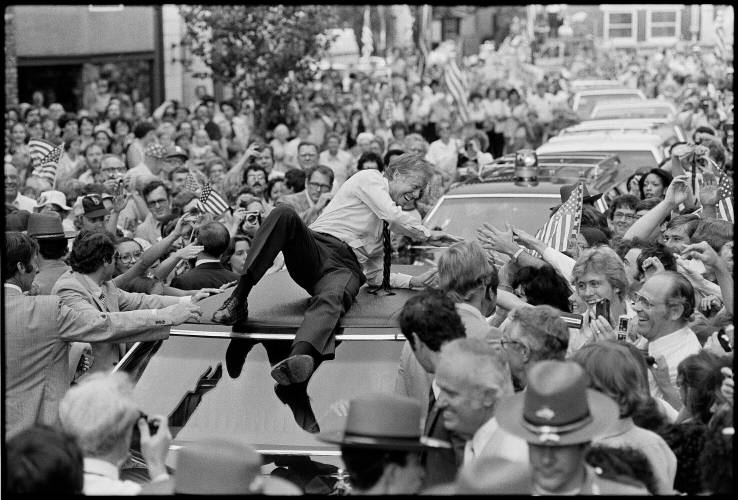

Jimmy Carter, the nation’s 39th president, died at 100 on Sunday, and for Pioneer Valley residents, he may be remembered for a great deal more than four bruising years in the White House.

“He was the greatest former president in the country’s history. Lived a truly honorable life,” said South Hadley’s Bill Foley, past chair of the town’s Democratic Committee, who started out canvassing for future House Speaker Tip O’Neill in the 1950s. “Carter may have been too good a person to be a great president.”

“Jimmy Carter was intelligent, compassionate and truthful — who knew how much we’d miss those basic human qualities?” asked ACLU attorney and Northampton talk show host Bill Newman. “He was unfairly treated historically. That may change. We didn’t know about the sabotage pursued on behalf of the Reagan campaign. And pardoning Vietnam draft evaders on his second day in office was not a universally popular decision, but he did it because it was the right thing to do. He had a backbone of steel.”

Of the Camp David Accords, where Carter brought Israel’s Menachem Begin and Egypt’s Anwar Sadat together until they hammered out what led to the Egypt-Israel Treaty of 1979, Newman said, “The odds of that were infinitesimal, but those two antagonists found Carter to be an honest broker who cared about both their people.”

But then you have Carter’s boycott of the Moscow Olympics after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

“Carter took the heat for doing it,” said Newman, “and you have to wonder, where did he get the unilateral right to do it? I don’t know if there was a better solution.”

“He was a victim of the power elite, and like the phoenix, emerged as a light, doing so much good out of government,” said CodePink peace activist Paki Wieland of Greenfield. “He boldly stood up to the fossil fuel companies, so they found Ronald Reagan.

“Then he founded The Carter Center and facilitated peace and justice-making across the globe,” Wieland continued. “Jimmy Carter was a man of conscience! Let his life inspire and encourage us who can do so much, out of government.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Greenfield Starbucks provides update for opening day

Greenfield Starbucks provides update for opening day

Shelburne Falls veteran pleads guilty to stealing benefits, lying about service

Shelburne Falls veteran pleads guilty to stealing benefits, lying about service

Div. 5 boys basketball: No. 1 Pioneer stifles Drury to cruise into state title game following 49-23 semifinal victory (PHOTOS)

Div. 5 boys basketball: No. 1 Pioneer stifles Drury to cruise into state title game following 49-23 semifinal victory (PHOTOS)

Dog retrieved after fall through ice in Northfield

Dog retrieved after fall through ice in Northfield

Greenhouse fire in Deerfield may have started with extension cord, chief says

Greenhouse fire in Deerfield may have started with extension cord, chief says

Hager’s Farm sugarhouse fire quickly extinguished in Colrain

Hager’s Farm sugarhouse fire quickly extinguished in Colrain

“He was a good human being and a good leader,” said Northwestern District Attorney David Sullivan, who cast his first presidential vote for Carter in 1980. “I thought he deserved another term. But he was hit by forces out of his control — the oil crisis, the Iran hostages, inflation.

“I wished he had more of a chance, but we can predict elections by how the economy goes,” he added.

Of Carter’s strained relationship with Congress, Sullivan said, “I don’t think people appreciated the supermajority in Congress they had. If he’d collaborated with Tip O’Neill, he would have gotten more done.

“The time after his presidency is how we should judge Carter. He dedicated his life to peace and helped people with housing, that most essential part of life. And he was smart,” added Sullivan. “We need to go back to presidents who are smart.”

“Jimmy Carter’s presidency wasn’t appreciated at the time, but it was consequential,” said Northampton’s Bill Scher, political editor for the Washington Monthly. “He forged lasting peace between Israel and Egypt. He ended America’s unjust control of the Panama Canal. He established the Department of Energy, the Department of Education and … with his appointment of Paul Volcker to chair the Federal Reserve, he put in place the plan that ended years of runaway inflation. That’s not too shabby for a one-term president.”

But some of those very memories remain painful.

“Jimmy Carter, like Barack Obama, was a fresh face with a solid background in the military and as Georgia governor,” the late Williamsburg author and retired auto dealer James Cahillane said in an interview before he died. “But my strongest memory of President Carter is of 1970s high interest rates. A crushing $20K a month for inventory alone at our small Dodge/Jeep dealership!

“I didn’t vote for him, but believe that’s why Ronald Reagan won Massachusetts, by a whisker, in the 1980 election,” he said.

“I think of Jimmy Carter as a better human being than he was a president,” said sportscaster Scott Coen of Northampton. “I’m old enough to remember the inflation rates of the 1970s, although I wasn’t necessarily paying the bills at that time. I definitely remember the long gas lines, the Iranian hostage crisis and the botched rescue attempt. But when Carter left office, I admired his ability to be a citizen of the world. He in many ways seemed to become our conscience.”

“He was exactly what we needed after Watergate,” said former Northampton City Council President Bill Dwight. “He was bracketed by the cynical presidencies of Nixon and Reagan. He was candid. He spoke of a great malaise, initiated the 55 mph speed limit, none of which washed with large segments of the population — ‘Hey, stop telling us how we should behave better!’”

As for his conciliatory stand on segregation as a rising politician in the Deep South, Dwight said, “Jimmy Carter didn’t eliminate racism, but initiatives and policies were put in place to weaken it. Like LBJ coming up in Texas, they had to navigate the waters they were in. The Black leadership now seen in Atlanta — that wouldn’t happen without Jimmy Carter.”

As for Carter’s post-White House years, which began at 56: “He didn’t go on speaking tours,” said Dwight, “he went and built houses for Habitat for Humanity. And lived with Rosalynn in their modest home back in Plains.”

“He inspired so many,” said Megan McDonough, executive director of Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity. “It’s a joyful thing, working with people. You can’t underestimate the impact of the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Work Project, and the people drawn to it. Such a huge need, housing.”

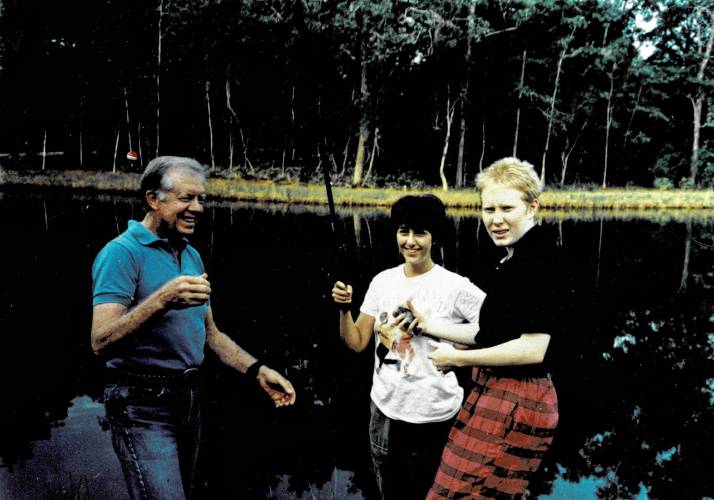

MJ Adams, former head of Greenfield’s Community and Economic Development Department and former executive director of Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity, worked side by side with the Carters on five different builds, some on other continents. “Highly unskilled volunteers with good hearts,” said Adams. “In Edmonton we built homes for refugees from Afghanistan.”

Adams described the Carters as “no nonsense bosses. Some people want to get autographs and pictures taken with the president. He’ll say, ‘Get back to work!’ He expected us to be exhausted by the end of the day.

“A marvelous thing. At the end of the week, the houses are dedicated. He was so incredibly present talking to those families, as if no one else exists in the world.

“Everyone, especially children, deserves a safe decent place to call home,” said Adams, grateful to Carter for putting such ideas in her head.

One of Northampton’s many moments in the national spotlight came in 1986 with the trial of Carter’s daughter Amy, then a sophomore at Brown University, and 1960s radical Abbie Hoffman on charges of blocking CIA recruitment on the UMass campus. One of the 13 co-defendants at the trial was current Northampton City Councilor Rachel Maiore, then a UMass freshman.

“I first met Amy Carter when she crawled through a window at Munson, the building we were occupying,” Maiore said. “We’ve been friends ever since. Amy had moral grit before a lot of us did. She was raised with those kinds of values. Mr. Carter called Amy when we were acquitted. He was very proud. I’d go to their house in Plains, smaller than a lot of my friends’ houses. He’s just like you’d think he’d be — out there making furniture, totally guileless, an evolving guy, really open.”

One issue that almost saw the light of day during Carter’s time in office but ended up taking 40 years was the legalization of marijuana.

“It was August of 1977,” said Northampton attorney Dick Evans, who fought for decades to change drug laws. “Until Obama, Carter was the only president with the courage to acknowledge the injustice of marijuana prohibition. He boldly declared: ‘Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself.’”

A brief window of optimism soon slammed shut.

In December of that year, Evans attended the national NORML conference in D.C. “The smoke was thick and trays of joints were passed around,” said Evans. Then, up the stairs, in suit and tie, came Dr. Peter Bourne, Carter’s drug policy adviser.

“I remember saying to myself, wow, I’m in the right place with the right crowd, more confident than ever that marijuana reform was just around the corner. Several months later, on a Saturday morning, I opened the New York Times to read that Bourne shared some cocaine in that room. That was the moment, it was later said, that the entire marijuana reform movement went up Peter Bourne’s nose,” said Evans. “Carter was a peacemaker … but sadly his efforts to curb Nixon’s drug war were thwarted.”

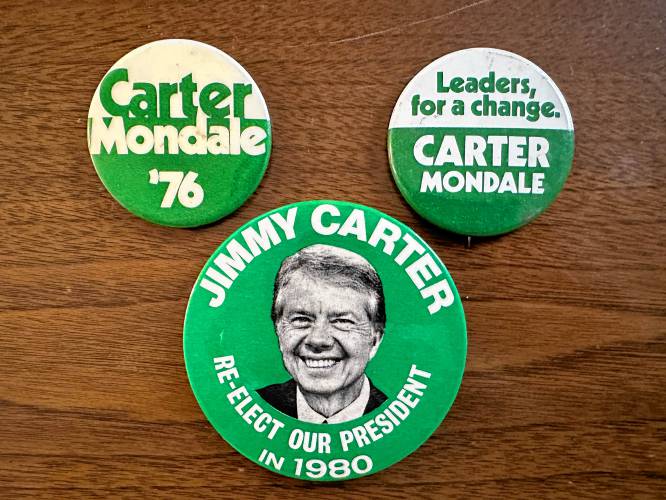

The 1976 election between President Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter was a tight one, the smiling Georgian prevailing 297-240 in the Electoral College. An elector in that race was Northampton’s Phil Sullivan, former city councilor.

“Well, I was disappointed,” Sullivan said of the Carter presidency itself. “He was honest, believed in everything he said, if a little misguided. But he seemed like a guy you could sit and have a drink and cigar with.”

Greenfield Starbucks pours its first cup

Greenfield Starbucks pours its first cup Charlemont officials throw support behind potential education funding lawsuit

Charlemont officials throw support behind potential education funding lawsuit Interested firms visit Carnegie Public Library in Turners Falls to learn plans

Interested firms visit Carnegie Public Library in Turners Falls to learn plans