Record-breaking athlete turned renowned artist: Peter Ruhf, whose work is on display at Greenfield’s TEOLOS gallery, was once a boomerang champion

Peter Ruhf took up boomerang throwing after pitching a perfect game at age 21. He went on to become world champion several times and, with his twin brother, Larry, helped to popularize the sport throughout the U.S. and Europe. Courtesy Ellen Saxe

| Published: 03-28-2025 10:19 AM |

Last week’s column featured Peter Ruhf, multimedia artist and philosopher. This week, we delve into Ruhf’s unusual upbringing and influences. By the time this goes to print, some will have attended the March 28 opening reception of “The Visionary, Surrealistic, and Psychedelic Art of Peter Ruhf” at Greenfield’s TEOLOS gallery. Those who missed it can take heart: the show runs through April 26.

Peter Ruhf and his twin, Larry, grew up alongside twin cousins Barnaby and Ed, who were seven months their senior. When Peter and Larry took up throwing boomerangs, Barnaby tried his hand, too, eventually perfecting the stunt of throwing a boomerang so that it returned to knock an apple from his head, whereupon it split in two. “Barnaby rigged it,” said Ruhf. “He sliced the apple ahead of time and stuck it back together with toothpicks.” Given that throwing a boomerang so that it returns to an apple sitting atop one’s head requires exquisite skill, it hardly seems like cheating. “It’s not that hard,” said Ruhf, whose name appears in multiple editions of the Guinness Book of World Records. (Easy for him to say!)

Peter Ruhf mastered the stunt, too: “It put me on the cover of Life magazine.” The boomerang phase grew out of other outstanding athletic abilities: a champion wrestler and all-star lefty pitcher, Peter pitched a perfect game at age 21. For those unfamiliar with the sport, a perfect game is one where no runners reach a base by hit, base-on-balls, or error – one of the game’s rarest feats. “Larry was also a stand-out ball player,” said Peter. “Larry looked up how to pitch a curveball; he read me instructions from a book, and I mastered it.”

After his twin pitched a perfect game, Larry joked that maybe Peter should take up the boomerang. The comment wasn’t such a stretch, given that two of their uncles had connections to Australia. Edward Ruhe (not to be confused with Ruhf) was a renowned collector of aboriginal art, and Ben Ruhe spent time in Australia during the 1950s. Uncle Ben later organized boomerang events on the National Mall in Washington, bringing many people into the sport. In the mid 1990s, a Ruhe/Ruhf nephew, Adam, who grew up in Amherst, set a world record at age 16. (Note: Anyone feeling confused about Ruhe/Ruhf, please consult part one of this series.)

Peter Ruhf was highly motivated to pursue excellence: “I was born with a club foot, and struggled since birth. Some thought I would never walk properly. I had a great impetus to get strong, and my siblings were very proud of me.” When he got his hands on a boomerang, he nailed it, and he wasn’t alone in that pursuit: Larry was a pioneer in the sport of competitive boomerang throwing, and in 1981, competed on the first USA boomerang team against Australia. Larry organized the first-ever International Team Cup in 1987 and was also a national champion and world record holder. The brothers toured Europe, attracting fans and competitors to the sport. Larry went on to become a respected innovator in the field of psychology, working in Holyoke and Northampton: later in life, he became an accomplished painter, sculptor and musician. These guys didn’t mess around.

In 2021, Peter Ruhf lost his beloved twin, with whom he shared a Buckland home. “I was devastated,” he said. “One morning, Larry didn’t come down for coffee. I found him in bed; he was gone.” The twins had lived separate lives while existing in intertwined modes, as well. “We were very different,” said Peter. “Larry was thin, a chatterbox, and an intellectual. I was muscular, heavier.” Peter was no lightweight in the brains department, however: “I graduated summa cum laude from college. My parents couldn’t believe it.”

Peter and Larry attended the University of Michigan, where Larry majored in psychology and Peter majored in art. Yet Peter studied psychology, as well. “I was fascinated by the human mind,” he said. “Our older brother – a brilliant guy – had a psychological break as a young man, and never recovered. It affected us deeply.” In a family where intensity was a hallmark, there were both light and dark sides.

Ruhf fondly recalled his maternal grandfather, Percy Bott Ruhe, who for six decades was editor of the Allentown Morning Call newspaper. “He was remarkably erudite, a valedictorian,” said Ruhf. For Peter Ruhf, the combination of brains and brawn was a winning combination that led not only to victories, but to successful entrepreneurship as well. “Because I’m a lefty, I made my own boomerangs,” he said. “That grew into a business where I made and sold hundreds of boomerangs.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

How did a world champion athlete become a renowned artist whose work is on display at a local gallery? “I painted every single day for the last 60 years,” said Ruhf. Discipline and focus served him well in the artistic realm. “After Larry and I graduated from college, we drove to Berkeley. Our sister, Robin, taught at an alternative school out there. My family was very improvisational, and my sister was one of my idols.” Ruhf’s time in the Bay Area was filled with artistic exploration, which led to “big shows in New York City, Washington DC, and places like that.” Between the boomerang factory and creating visual art, Ruhf was able to “pay the bills.” After relocating to western Massachusetts, Ruhf sometimes did another kind of painting: “Interior and exterior house painting,” he said, “which is incredibly hard work.” Yet even then, Ruhf was called upon to produce murals and mosaics. “Someone would ask me to paint their ceiling with images, and I would do my thing.”

Peter Ruhf has been doing his thing for nearly eight decades, facing each day with skill, creativity and courage. “In terms of aging, I’m like a fine wine,” he said. “The older I get, the more meaningful my painting becomes.” Ruhf’s work is up at the TEOLOS gallery, 3 ½ Osgood St. in Greenfield, from 3 to 6 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays through April 26.

Eveline MacDougall is the author of “Fiery Hope” and a musician, teacher, and mom. To contact: eveline@amandlachorus.org.

For the love of peanut butter: April 2 is National Peanut Butter and Jelly Day

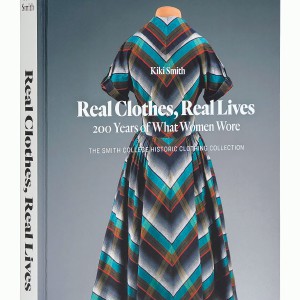

For the love of peanut butter: April 2 is National Peanut Butter and Jelly Day Women’s history told through clothing: Shelburne Falls Area Women’s Club to host ‘Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore’ author, April 9

Women’s history told through clothing: Shelburne Falls Area Women’s Club to host ‘Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore’ author, April 9 Valley Bounty: And on that farm she had a bit of everything: Little Brook Farm in Sunderland is a labor of love for farmer Kristen Whittle

Valley Bounty: And on that farm she had a bit of everything: Little Brook Farm in Sunderland is a labor of love for farmer Kristen Whittle ‘A woman who should be remembered’: New play about the life of Frances Perkins, the brains behind FDR’s New Deal, April 5 and 11

‘A woman who should be remembered’: New play about the life of Frances Perkins, the brains behind FDR’s New Deal, April 5 and 11