A moment with Dr. Fauci: Expert who became household name during pandemic featured guest at Amherst College LitFest

|

Published: 03-04-2025 10:16 AM

Modified: 03-04-2025 3:35 PM |

AMHERST — When the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report landed on Dr. Anthony Fauci’s desk in June 1981, he had no idea it would be the start of a “dark” period of his career.

A similar moment would come 40 years later, on New Year’s Day 2020, when a journalist tipped him off to news about a pneumonia popping up in China — a pneumonia that would soon be known as COVID-19 and catapult Fauci into a household name.

In his role as director for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) for a four-decade period that ended in 2022, Fauci became a generational expert and one of most prominent faces of the past decade due to his role in tackling two of the biggest health crises of the past century: COVID and AIDS, or Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

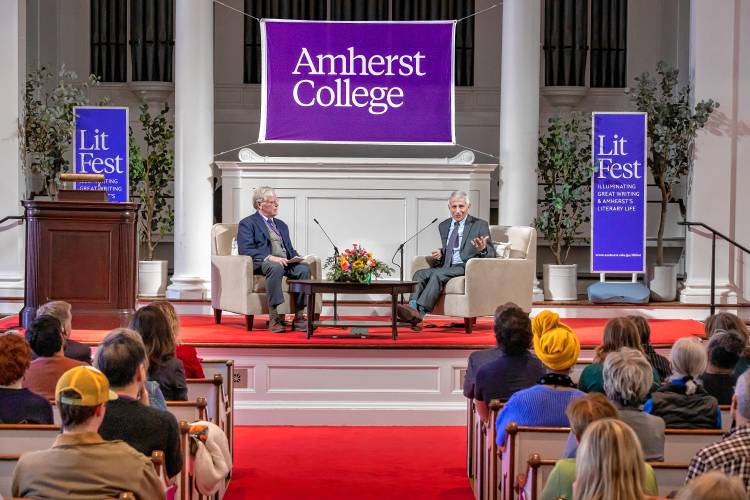

On Sunday, the 84-year-old was a featured speaker on the final day of LitFest at Amherst College, sitting down for a one-on-one conversation with Cullen Murphy, a 1974 alum and former managing editor with The Atlantic Monthly, viewed by some 600 people who filled the Johnson Chapel.

The first “dark” period of Fauci’s career started in 1981 with the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, prepared by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), noting that five gay men had come down with pneumonia.

Fauci didn’t think too much of the information until a month later when more cases popped up, and the report showed 26 young and previously healthy gay men had died. The report prompted him to drop the research work he was doing at the time and pivot toward investigating this new disease. Many around him, however, considered it to be a “foolish pivot.”

“Don’t give up your day job, it’s going to go away,” Fauci said his mentor told him at the time.

But rather than going away, AIDS was just beginning. The epidemic would end up taking the lives of 42.3 million people worldwide since its beginning in the early 1980s.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Two arrested on drug trafficking charges in Greenfield

Two arrested on drug trafficking charges in Greenfield

Berkshire DA says no crime occurred in student-officer relationship at Mohawk Trail

Berkshire DA says no crime occurred in student-officer relationship at Mohawk Trail

Four Red Fire Farm workers arrested as part of ICE operation in Springfield

Four Red Fire Farm workers arrested as part of ICE operation in Springfield

Incandescent Brewing now open in Bernardston

Incandescent Brewing now open in Bernardston

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Local ‘Hands Off!’ standouts planned as part of national effort

Proposed ordinance would make Greenfield a ‘sanctuary city’ for trans, gender-diverse people

Proposed ordinance would make Greenfield a ‘sanctuary city’ for trans, gender-diverse people

“I felt a phenomenal degree of empathy for these suffering and frightened, young almost exclusively gay men, who already were disenfranchised in society with stigma, who were now coming to the hospital and dying, seven, eight, nine months later,” Fauci said.

Fauci said that as a doctor it was a difficult balancing act to weigh both the “pristine nature of a clinical trial” that could take years before development of a treatment plan and the need to listen to victims of the disease that demanded treatments immediately.

“They were very provocative,” Fauci said, referring to AIDS victims and their advocates. “They were very attacking. They were right. And that I think is the biggest lesson I learned from that.”

He continued, “It took years of back and forth, negotiating with them and getting them to understand, and they provided some of the most productive input into how we design clinical trials into the regulatory process.”

Then came 2020. Ten days after a journalist asked him about some unusual pneumonias in China the search for a vaccine began, despite the fact that experts weren’t overly concerned initially.

Fauci’s first consultation with colleagues unveiled it had probably been SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which broke out in 2002, but was hardly contagious.

“There were about 8,000 cases and 781 deaths and then it disappeared,” he said.

“So in the beginning there was this feeling that it wasn’t horrendous, but since I was the head of NIAID, one of the responsibilities was to roll out vaccines for these,” he said.

That vaccine effort led to “Operation Warp Speed,” which the Trump administration launched in May 2020 to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines, and would push the limits of how fast a vaccine could be produced.

“And you know that the story is that we developed the vaccine that, together with the pharmaceutical companies and the billions of dollars put into Operation Warp Speed, we got a vaccine available in 11 months,” Fauci said. “And for those who know anything about vaccines, it usually takes about seven to 10 years. But given the fact that it was being tested in the middle of an explosive outbreak, we were able to get an answer, which was a vaccine that was 93 to 94% effective.”

Murphy asked Fauci if he’d do anything differently, now that society is nearly two years past the end of the pandemic.

Fauci said that many in the public interpret changes to care as “flip-flopping,” but in reality it’s the self-correcting process of science. His projects, he said, have featured repeated “moving targets,” which has made pinning down care even more difficult.

“If I knew in January 2020, I would have done and said a lot of different things,” he said, which includes recognizing masking as an essential right from the get-go of the pandemic.

Fauci has served as an adviser to every president since Ronald Reagan. While most recently Fauci may seem to represent an antagonistic force against President Donald Trump due to their disagreements over the pandemic, he said that was never his goal.

But the infectious disease expert felt compelled to speak up when faced with misinformation.

“When the press asked me, ‘Is it true that the virus is going to disappear like magic’ after the president just said it was going to go away like magic ... I had to do something very uncomfortable. I had to disagree with the president of the United States,” he said.

The doctor says speaking up like this has changed his life in a number of ways, including “an extraordinary avalanche of vitriol” against him.

“I have a phenomenal amount of respect for the institutions in this country, including the presidency of the United States, and it was very, very painful for me to have to publicly, honestly answer a press person and say, ‘No, this is incorrect,’” he said.

“I just felt in order to protect my own personal integrity, but even more important, or as important, as to fulfill my responsibility to the American public.”

Despite the backlash and threats, “If I had to do it over again I’d do it,” he said.

In one of the few moments where Fauci addressed current political events, he said the “decimation” of USAID “is going to have a major impact on people who need drugs to save their lives.” He added that, “A lot of people are going to die that shouldn’t die.”

He also said the skepticism about vaccines expressed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Trump’s secretary of Health and Human Services, has “no basis in fact or data.”

Fauci also spoke of his dad’s “very poor business model” as a pharmacist, and of his educators for giving him a foundation based on principles of serving others. He talked about learning about service from priests and nuns from Catholic schools as a kid, and said public service is about more than politics specifically citing teachers.

The Fauci family, an Italian immigrant family in the Bronx, was described as not too well-off financially, which made a young Fauci curious why his dad would let people ring up tabs he knew they wouldn’t pay. “They’re struggling more than we are,” his dad would say.

He said service also was paramount at Regis High School, where he played as the 5-foot, 7-inch point guard and captain of their varsity basketball team. While the school was highly competitive, an all-boys school at the time that only accepted students with scholarships, the school also was oriented toward service, having a motto of “Men for others” at the time.

Near the end of his conversation on Sunday, when asked about the hardest experience of his career, Fauci recalled an optimistic and well-mannered patient who was suffering from cytomegalo virus, which burns away at the retina. Each day during his rounds, the patient would greet him: “Hi Dr. Fauci, it’s great to see you.”

A few weeks later, the patient, now blind, greeted Fauci with a “Who’s there?” — something the doctor called one of the most excrutiating experiences of his career.

Literacy Project celebrating 40 years of education

Literacy Project celebrating 40 years of education River Rat Race returns for 60th year on April 12

River Rat Race returns for 60th year on April 12 Backyard Oasis, connecting older adults with podcasts, celebrates 50 episodes

Backyard Oasis, connecting older adults with podcasts, celebrates 50 episodes